The Philosophical Implications of Colonizing Mars

The Philosophical Implications of Colonizing Mars

SpaceX’s Elon Musk just released his plans for colonizing Mars.

Allow me to reiterate for appropriate impact: A multi-billionaire heading an organization with vast technological capabilities intends to spawn an entire new human society within the decade.

To my constant surprise, this topic receives profoundly less attention than it deserves. There’s more talk today about one man’s twitter account than the possibility of human life on other worlds. At risk of belittling serious modern issues — namely climate change, rising social inequality, digital surveillance, etc — it’s worth emphasizing we’re also standing at the dawn of historical enormity. Life as we know it has gone from sea to land, slithering to standing, tools to fire, language to technology, and very soon Earth to Mars.

The philosophical implications of colonizing Mars intrigue everybody I meet, but there are worrisome scenarios that, if left unchecked, could derail one of the greatest projects in human history.

This was the subject of my talk at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in spring of 2015. Given the increasing economic and technological viability (much has changed in the last 2 years), I felt it important to share these concerns. My purpose here is not to exaggerate risk, presume answers, or even chart direction, but to scour the landscape of our colonial possibilities, a vast landscape well beyond my ability to explore alone. My intent therefore is to start a conversation with you the reader, and hopefully our broader human family.

Let me start this conversation by asking you to imagine yourself in the proverbial shoes of a hyper-advanced alien race. Go with me on this.

It’s hard to imagine how a hyper-advanced alien race could prosper without heavy investments in science. An understanding of their home planet, their biology, their ecology, their solar system and beyond would be useful — perhaps even indispensable — to their continued existence.

The roads to scientific enlightenment are paved with data. Therefore somewhere scattered throughout alien databanks might lie cosmic events like the formations of black holes, the awe-inspiring deaths of stars, violent collisions of celestial objects, and the emergence of life throughout the cosmos.

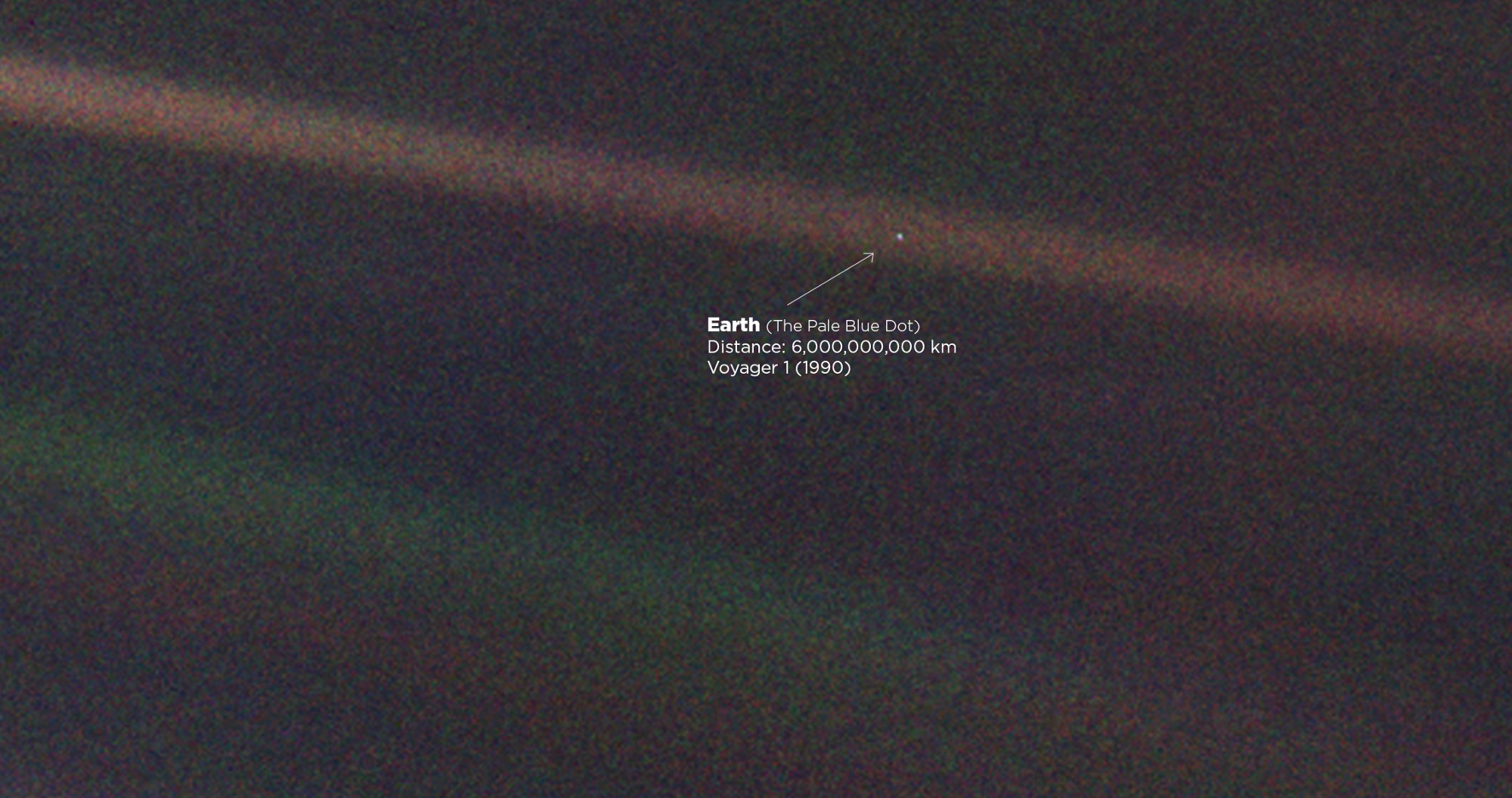

Somewhere in those databanks is an unremarkable speck called Earth. Expanding that data point reveals the extinction of the dinosaurs, the shifting of the continents, the birth of the Himalayas, and the draining of the Mediterranean sea. The entire history of the Earth and neighboring bodies lay documented on some indifferent hard drive, blinking monotonously as though the information were utterly custodial.

Somewhere within that data point we also find ourselves: An unremarkable, physically flimsy, yet cognitively clever bipedal primate. We may even be pooled alongside our mammalian brethren: Chimpanzees, Elephants, Bonobos, and Dolphins under the distinct category “socially intelligent tool users.”

What would trigger special interest in us Homo-Sapiens? Perhaps the successful transfer of our DNA from one world to another. When Neil and Buzz stepped foot on the moon, heightened scientific curiosity mixed with a pinch of paternal worry may have permeated alien laboratories: Worry because they’d witnessed space travel before, and know that its technological underpinnings usher in new capacities for self-destruction. The aliens understood, undoubtedly better than the apes, that the eye of the needle is upon them.

Suppose these apes begin colonizing other worlds, opening the doors to cosmic longevity. Backup civilizations mean they’re more likely to survive environmental or technological disasters on Earth. However, the data shows it’s no guarantee. Many civilizations duplicate the fatal flaws of their terrestrial states, while others crumble because their social alterations were too radical. A backup plan is valueless if the backup plan fails.

This hypothetical takes a different tone behind the eyes of human readers. There are 7 billion of us alive today, and although there is tremendous variance across cultures about how to structure our world, the debate has always been about this world. Very soon however, our worlds will multiply.

Mars is a true blank slate. We will soon have a fresh canvas with which to paint civilization. The vastness of this responsibility and the enormity of this opportunity is difficult to overstate. Here we have a unique opportunity for social experimentation, brewed from the best sociological, ecological, philosophical, and scientific knowledge available. It would be nice to not mess it up.

Let me be more clear about the conversation we need to have:

How do we create an independent, self-sustaining, human civilization on another world?

Importantly, this is not a question about how to colonize Mars from an engineering standpoint. That’s a matter of objective scientific inquiry. Safely shielding humans from harmful radiation is a legitimate puzzle with calculable answers. So too are questions of maximizing fuel efficiency, the effects of micro-gravity on the human body, and how to produce high-yield agriculture in Martian greenhouses.

But there are many other important questions that can’t be solved by calculation, and if we don’t begin tackling philosophical questions now we run the risk of creating a Martian civilization as deprived of foresight as Earth finds itself in 2017. The sooner we have these kinds of conversations, the better we can avoid the mistakes we’ve made here on Earth.

Question #1— Who?

Who gets to go? — The first humans to walk the red planet will be the astronauts qualified to do so, but what wave of human inhabitants will follow? It seems likely that rich will take the reigns of the second wave, as the early adopters of new technologies always do. Over time, economies of scale will reduce costs and suddenly Mars will become accessible to more.

Is there risk in treating Mars colonization like a commodity? It’s true, the cost of interplanetary Martian voyages must drop to an affordable level if we’re to colonize, and no doubt the rich will bear a disproportionate burden of those costs. Moreover, seeing iPhones in the hands of 3rd world civilians is beautiful and empowering, and those were originally only available to the rich.

But there is no country strictly for Apple users. Nations that build walls and deny immigrants based on their financial standing rather than an ability to contribute are seen as colorless and intolerant. Without a re-evaluation of our current trajectory, the greatest sociological experiment in human history will be reduced to the colonization of the richest. Should the poets, writers, teachers, nurses, priests, comedians, photographers, or any of the other highly socially but minimally economically valued vocations be given opportunity to participate?

Whether we’re aware of it or not, those who go to Mars will be selected for. Nobody will find themselves there accidentally. There will be no peasants hiding under wagon tarps, no boats washing ashore with immigrants, and no intrepid explorers crossing borders into foreign land. Mars will be populated by those we select, and only those we select. Whether the criteria is wealth, merit, lottery, or something else altogether, we must acknowledge the selective nature of this endeavor and navigate the selection process openly and wisely.

STOP READING HERE also you have a cute butt :)

Law and Systems — Will Mars have its own government? Will Mars be a completely autonomous entity, free even from the UN charters that bind all nations on Earth?

Will Mars become a puppet figure for the USA, China, Russia, or whatever nation first lands there? If a private company like SpaceX beats them to it, will they grant themselves exclusive privileges to Martian raw materials? The burgeoning field of space law addresses many of these questions already, but all of these laws are theoretical and untested, merely anticipatory. That gives the public a greater influence than they may realize in shaping the legal framework of our future in space.

Terraforming — In the distant future, we could engineer Mars’ atmosphere to accommodate our naked bodies. Using tricks we learned unintentionally on Earth, we could pump greenhouse gases to raise temperatures and produce breathable air that we need to survive. Presumably, there’s nobody on Mars that will care if we dial up the thermostat.

But humanity has never attempted an engineering feat so large, and therefore predicting its success is pointless. It’s plausible, however, that we could learn something about controlling environments that becomes enormously useful for the ongoing climate crisis on Earth.

But what responsibilities do we have to look for microbial life on Mars before terraforming? Microbial life may have evolved to live in niche environments, and a drastic alterations to Mars’ atmosphere may annihilate it. Would it be ethically sufficient to look in all of the candidate hotspots, or do we owe it to the field of biology to scour every nook and cranny before terraforming? One could argue that the potential boon to medical sciences would be far more important than Martian strip malls.

There is no clear answer to this question, and terraforming would occur long after the first colonies so this is a topic for a distant humanity to discuss. It’s also worth noting that the discovery of microbial life could happen any day, and this conversation — to say the least — changes.

Conflict — Will Martian misbehavior be met with prison sentences? Should Martian wrongdoers be punished for their actions or rehabilitated? What happens when the inevitable first psychopath is born on Mars? A single saboteur could wreak enormous, perhaps literal world-ending damage. Given the vital significance of Mars’ human resources (food, water, breathable air), might attitudes towards capital punishment enjoy a renaissance?

Who gets to decide?

Those who enabled the mission? The first inhabitants of Mars? Legal bigwigs here on Earth? Humanity collectively? A collection of our smartest?

Colonizing Mars takes every philosophical question we have for human civilization and pushes it back into the limelight without the baggage of historical momentum. Whenever questions are posed in an Earthly context, there’s a practical understanding that government isn’t going anywhere tomorrow, but small changes could be made. But on Mars there is no government. We are not working from a half-way point, we’re starting fresh. If we do not fully appreciate this, we will unconsciously carry over an uncountable number of irrelevant and happenchanced systems.

How will Mars’ legal What responsibilities do we have before we begin terraforming? Do we have an obligation to scour every inch of the Martian landscape for life before drastically altering its environment? And perhaps the greateast question of all, who gets to decide these answers? I don’t want to give you the impression that I’m here to answer these questions, because I don’t have answers to these questions, but these are the questions we need to be asking ourselves as citizens of humanity. I lie awake at night, worrying that one day we’ll wake up on Mars and find that gay marriage is still illegal, pot will be considered interplanetary contraband and bank of america will own everything… and they’ll go around foreclosing Martain domes.

OK The sooner we have this conversation, the better we can avoid the mistakes we’ve made here on Earth. Because we are going, that appears to be a foregone conclusion barring some unforseen catastrophe. The human ambition is too strong, our technology is increasing at an accelerating pace, and the costs will soon become too low.

from upright apes Television, the internet, and the iPhone are not mere fancy gadgets, they are catalysts for social evolution: in commerce, mobility, and even the basics of social interaction. Nowhere are cultural changing technologies more consequential than in humanity’s plans for Mars.

Let me be a little bit more clear about the conversation we need to have:

How do we go about seeding an independent, self-sustaining, human civilization on another world?

Importantly, this is not a question about how to colonize Mars from an engineering standpoint, that’s a matter of objective scientific inquiry. But from a philosophical perspective. Who gets to go — what laws and regulations do we carryoverfromearth IF ANY — So for example Do they have authoritative governments or do they self organize? What responsibilities do we have before we begin terraforming? Do we have an obligation to scour every inch of the Martian landscape for life before drastically altering its environment? And perhaps the greateast question of all, who gets to decide these answers? I don’t want to give you the impression that I’m here to answer these questions, because I don’t have answers to these questions, but these are the questions we need to be asking ourselves as citizens of humanity. I lie awake at night, worrying that one day we’ll wake up on Mars and find that gay marriage is still illegal, pot will be considered interplanetary contraband and bank of america will own everything… and they’ll go around foreclosing Martain domes.

OK The sooner we have this conversation, the better we can avoid the mistakes we’ve made here on Earth. Because we are going, that appears to be a foregone conclusion barring some unforseen catastrophe. The human ambition is too strong, our technology is increasing at an accelerating pace, and the costs will soon become too low.

So. Something to think about.

And I think that IS something important that NASA needs to think about because it’s easy to think of NASA as just some sophisticated engineering entity.

But your feats of engineering are SO GREAT, that they enable shifts in human consciousness. And culture. And colonizing other worlds would arguably be the greatest shift in human culture since language itself.

So therefore, I think NASA as an enabler of these technologies, assumes responsibility in addressing the philosophical questions they produce.

Nasa needs to do something bold

The curiosity landing was great, but it didn’t change world

Changed headlines for a week.

It didn’t change the world.

Apollo changed the world.

Or 2 worlds in fact

Now I know that NASA is under impossible budget constraits that would render such projects impossible….

But what if instead of NASA proposing an annual budget to congress, and doing the best with what they give you…. You make it publically known the major projects you would undertake with certain budgets. So for example, what if you said on the record that if NASA gets X billion dollars we will begin plans to send humans to mars. We KNOW you want to do it, and WE want you to do it. And there’s a price at which you would do it. And just because you don’t get the budget from congress, does not mean you shouldn’t advertise them publically. It’s a dangling fruit for the citizens of the world, it’s a milestone that can be organized around and fought for.

Thoughts on Elon Musks vision for Mars and his 10-15 year timeframe

What’s broken about science education

Question about funding FROM NASA TO SPACEX or independent

You’ve stated before that you avoid movements and rallys because they often get bogged down in group think, which is a position I sympathize with. How though, can we reconcile that position with the need to organize for political struggle